Blog 4: Databasing name variations

Posted by Cam on 2019-01-17

“How much detail to keep?” is a perennial question when creating a data model for anything. Detail, comprehensiveness and flexibility trade off against development time, error-proneness, and query time. In the case of modeling the taxonomic relationships among names, one specific question is how to model name variation in a database’s structure. Name variation was discussed in the last blog: the “same” name can appear in different online resources with variation in its character string, preventing simple database-to-database lookup and linkage. I discussed ways to reconcile these string variations, and to assess, with a measure of confidence, if two name strings represent the same underlying name.

The two general approaches to modeling this name string variation in a database are: i) to maintain only a single canonical name for each published name and to resolve variation prior to entering names into the database, or ii) to preserve all name variation in the database and record the resolution of variation within the database. An example will make this clearer. If we want to record information about synonymy, we can either store data only about the synonym relationships among “canonical” names, or we can store the synonym relationships as we find then, and also record the name-to-name reconciliation:

Data Source X: Aaaa aaaa is accepted,

Aaaa bbbc is a synonym of Aaaa aaaa

Data Source Y: Aaaa bbbb

Reconciliation: Aaaa bbbb \ are variants. Aaaa bbbb is chosen as the

Aaaa bbbc / canonical form of the name.

Data model Canonical

approach 1: names Status/mapping Source (Optional notes)

========= ================= ====== ==================

Aaaa aaaa accepted X

Aaaa bbbb syn. of Aaaa aaaa X Present as “Aaaa bbbc”

in Src X

Data model All

approach 2: names Status/Mapping Source

========= ================= ======

Aaaa aaaa accepted X

Aaaa bbbb Y

Aaaa bbbc syn. of Aaaa aaaa X

Aaaa bbbc -> Aaaa bbbb Reconciled

Because full recording of data provenance is a core design element of this project, I have chosen to go with the second approach. However, this way adds a layer of complexity, as every query of the taxonomic relationship of two names requires that any orthographic variation be resolved as well (though this resolution may be pre-calculated and cached). E.g.:

Query Name ---[ortho]---> Variant Name A

|

synonym of

|

v

Result Name <---[ortho]--- Variant Name B

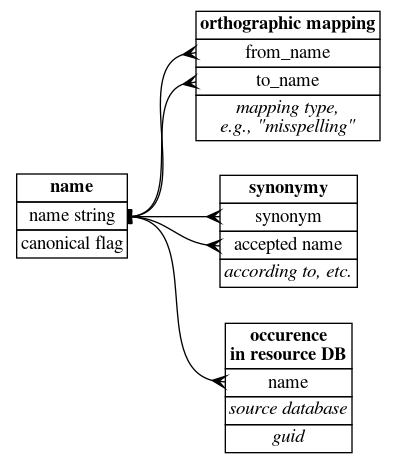

Although the (top) diagram shows a single data table, in practice, it seems conceptually clearer to have two tables: a taxonomic relationship table and an orthographic mapping table (especially since eventually we need to model the taxonomic relationships as concept-to-concept relationships, not just name-to-name relationships). So for the moment, my data modeling approach is this:

Also shown is a table that stores the presence of any name string in an online resource (IPNI, Tropicos, etc.) and the GUID associated with that name.

Canonical names

In the process of integrating different taxonomic resources and reconciling the names in them, I might attempt to reconcile “all with all”, requiring n!/(2*(n-2)!) combinations. While this would provide a useful resource for anyone trying to integrate across two arbitrary databases, it would take a great deal of time. The alternative I’ll take is to assemble a growing list of “canonical” name variants to which new resources are reconciled as they are integrated. These will also be the final names presented in the future Flora.

The choice of which variant to make canonical is somewhat arbitrary — is the abbreviated author’s name really “better” than the full name? So which name to chose? I had stated in the first blog post that we would use The Plant List as our reference set. Rod Page rightly took issue with this, asking “why not IPNI?” Unfortunately, IPNI does not contain all the names we may want (neither does The Plant List), so I’ve decided to use a hierarchy of sources to come up with our canonical names set:

- IPNI

- Tropicos

- WCSP (as found in The Plant List)

(I’d have liked to include the Flora of North America (FNA) in this list, probably at rank 2. There’s a team in Ottawa working on parsing and databasing the FNA accounts (including James Macklin, Jocelyn Pender, and Joel Sachs), and they have kindly given me access to the FNA names data, but it will take a while to come to grips with this resource. We will definitely link our Flora to the FNA work, and may include their names in the above canonical name list, but not quite yet.)

An aside: Use a graph database?

Since I first became enamored with RDF and the semantic web, I’ve kept an eye on graph databases, and played around with triple stores (4store, Allegrograph, StarDog, ClioPatria) and Neo4j and TinkerPop/Gremlin. I also have a frequently reoccuring desire to learn Prolog, and the conceptual similarity between querying triples and Prolog’s declarative pattern matching tempts me regularly to invest in learning ClioPatria, a Prolog-based triple store. So as it became clear that the flora project database would need to include name-to-name mappings, possibly in chains of arbitrary length, I wondered seriously if I should switch to a graph database for the underlying engine for this project. Gremlin, Cypher and SPARQL 1.1 (and Prolog) all allow for searching over arbitrary length property paths.

However, in the end I’m deciding to stick with a SQL RDMS solution, for reasons of familiarity, stability, speed, and hopeful longevity of the database. But what nailed it was discovering that MariaDB, which is my default choice of DB platform, now has Recursive Common Table Expressions, which permit following a data link chain of arbitrary length until some condition is met. So now I could query across multiple name-to-name orthographic mappings, if needed. Indeed, I hope I won’t need this (SQL is hard enough and ugly enough as it is!), but the facility is there.